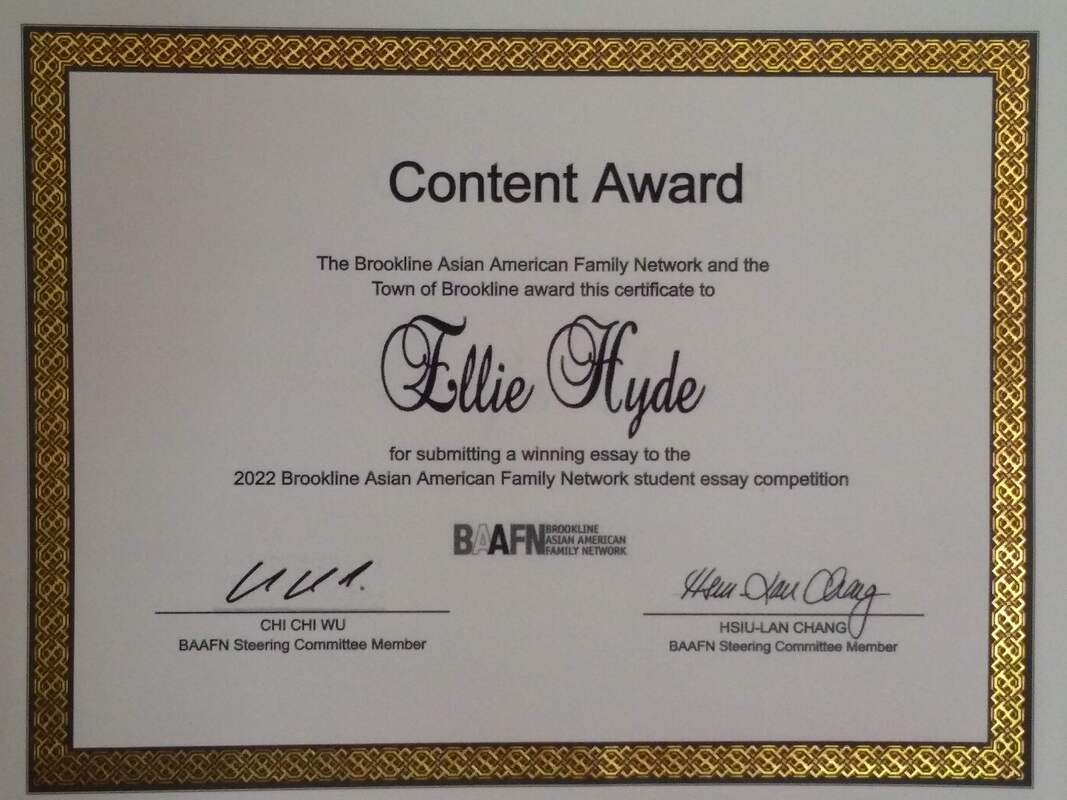

2022 BAAFN Content Award

Good Discomfort

by Ellie Hyde

It was at a violin lesson of all places, where I heard the most influential phrase of my life. I wasn’t particularly fond of the piece I was learning and had conveniently forgotten to prepare it. My teacher asked me why I was stumbling through the notes. One week was enough time to learn it. I admitted that I had barely touched the piece, and confessed that I disliked practicing it because it made me feel uncomfortable. I despised the way I wasn’t used to the strange fingerings, and how they made me feel like my fingers were getting tied into a giant knot. I loathed the tingle of frustration that I got when I shifted hand positions. Most of all, I hated how making mistakes made me feel. My teacher sighed and responded, “If you feel completely comfortable when you’re practicing, that means you’re not making any progress. Discomfort means that you’re challenging yourself. That you’re growing.”

I didn’t truly understand the gravity of what she said until I was doing a research project on Japanese war crimes.

Although I was raised in America, my maternal Japanese family had a great influence on me. They made sure to raise me to be proud of my heritage, and I was immersed in the language and culture. Unfortunately, I also picked up some of their ideological shortcomings−focusing on the present, and being ignorant of past injustices. Whenever I was in Japan and the morning news showed disputes between Japan and China or South Korea, my relatives would lament how China and South Korea kept bringing up the past. When I was younger, I had no knowledge of the history of Japanese actions in WWII. I did not know of the tens of thousands of women who were violated by imperial soldiers, nor did I know about the millions of innocent people murdered in the name of a divine emperor. I completely believed that Japan was innocent and China and South Korea were being unreasonable.

When Asian immigrants arrive in America, they are seen as nothing other than Asian. To someone who can not differentiate between the many countries in Asia, where you come from is the least of concern. Because of this, I had no pressure on me as a Japanese person to educate

myself on what my country was responsible for. I was immersed in a movement of pan-Asianism

and would always ask this: If we’re all Asian, why can’t we just get along? Why does anyone care so much about the past?

Imagine my discomfort as a junior, when I found a book in the library that held detailed accounts and images of the atrocities that the imperial Japanese army committed in Nanjing. Not only did that book prove to me that China and South Korea were not exaggerating about the past, it presented the hard-to-swallow pill that my country was not as flawless as I wanted to believe.

I could have put that book down. It made me beyond uncomfortable. I felt so ashamed to be from a country that committed atrocities. I closed the cover and placed the book back on the shelf, planning to deny everything I’d just read. As I tried to walk away, I felt a dizzying feeling of guilt crawl up my stomach, and the words of my violin teacher played in my head: “Discomfort means that you’re challenging yourself. That you’re growing.”

The idea of Japan’s innocence that I had known was false. All the information I had consumed in my life was now staring back at me, asking, Are you going to correct yourself now? Are you going to grow?

I picked up the book again.

Similar to unlearning a wrong technique on the violin, unlearning beliefs I grew up with was excruciating. More times than I would like to admit, I felt the same lukewarm sense of shame and guilt. I’m sure that I will feel it many more times as I continue to grow and educate myself. But this time, I know that discomfort is an opportunity for me to learn.

In America, I am Asian before my nationality, and so are my Chinese and Korean friends. However, if I want to be a positive part of this pan-Asian American movement, I must continue challenging my views and bettering myself. Understanding the past is the best way I can understand those near me, and that is the best way for us to be united as Asian American.

I didn’t truly understand the gravity of what she said until I was doing a research project on Japanese war crimes.

Although I was raised in America, my maternal Japanese family had a great influence on me. They made sure to raise me to be proud of my heritage, and I was immersed in the language and culture. Unfortunately, I also picked up some of their ideological shortcomings−focusing on the present, and being ignorant of past injustices. Whenever I was in Japan and the morning news showed disputes between Japan and China or South Korea, my relatives would lament how China and South Korea kept bringing up the past. When I was younger, I had no knowledge of the history of Japanese actions in WWII. I did not know of the tens of thousands of women who were violated by imperial soldiers, nor did I know about the millions of innocent people murdered in the name of a divine emperor. I completely believed that Japan was innocent and China and South Korea were being unreasonable.

When Asian immigrants arrive in America, they are seen as nothing other than Asian. To someone who can not differentiate between the many countries in Asia, where you come from is the least of concern. Because of this, I had no pressure on me as a Japanese person to educate

myself on what my country was responsible for. I was immersed in a movement of pan-Asianism

and would always ask this: If we’re all Asian, why can’t we just get along? Why does anyone care so much about the past?

Imagine my discomfort as a junior, when I found a book in the library that held detailed accounts and images of the atrocities that the imperial Japanese army committed in Nanjing. Not only did that book prove to me that China and South Korea were not exaggerating about the past, it presented the hard-to-swallow pill that my country was not as flawless as I wanted to believe.

I could have put that book down. It made me beyond uncomfortable. I felt so ashamed to be from a country that committed atrocities. I closed the cover and placed the book back on the shelf, planning to deny everything I’d just read. As I tried to walk away, I felt a dizzying feeling of guilt crawl up my stomach, and the words of my violin teacher played in my head: “Discomfort means that you’re challenging yourself. That you’re growing.”

The idea of Japan’s innocence that I had known was false. All the information I had consumed in my life was now staring back at me, asking, Are you going to correct yourself now? Are you going to grow?

I picked up the book again.

Similar to unlearning a wrong technique on the violin, unlearning beliefs I grew up with was excruciating. More times than I would like to admit, I felt the same lukewarm sense of shame and guilt. I’m sure that I will feel it many more times as I continue to grow and educate myself. But this time, I know that discomfort is an opportunity for me to learn.

In America, I am Asian before my nationality, and so are my Chinese and Korean friends. However, if I want to be a positive part of this pan-Asian American movement, I must continue challenging my views and bettering myself. Understanding the past is the best way I can understand those near me, and that is the best way for us to be united as Asian American.