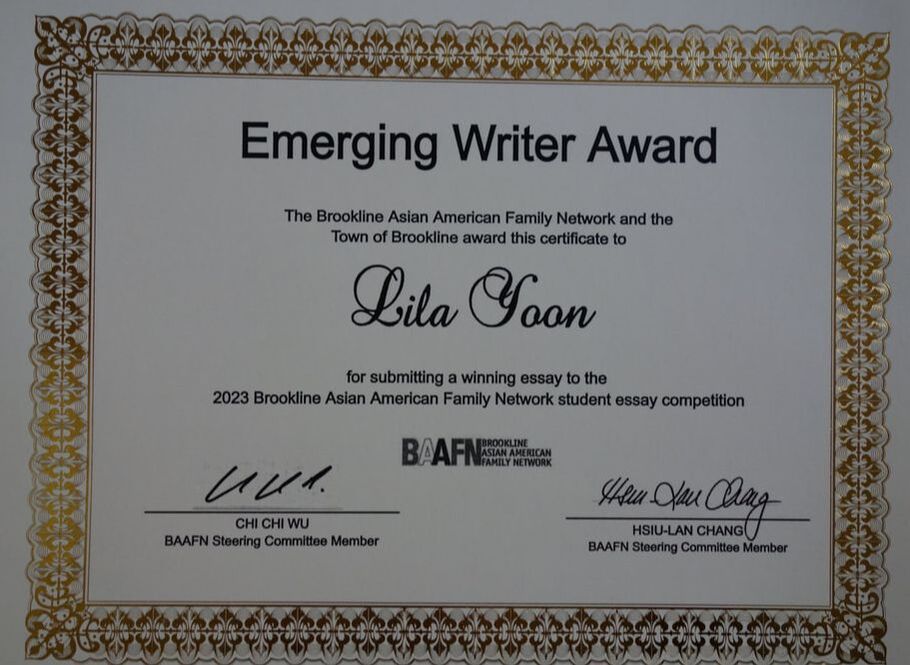

2023 Emerging Writer Award

Joy Is Resistance

by Lila Yoon

I find that home exists on either coast. My childhood memories sit hazily in the back of my mind; a pale orange couch and a smooth granite countertop, the sizzle of a frying pan and dumplings full of California-fresh vegetables, the smell of wonton noodles permeating a tiny New York living room as I fall asleep next to my brother. Despite being told in third grade that the lunch my mom packed me for school smelled, despite having eyes pulled back and nonsense chanted at me throughout middle school, I was confident in my Asian-American identity as a child. My happiest memories are so deeply rooted in my culture that to deny the validity of my heritage was to deny myself joy.

As the majority of this country begins to consider large concepts with such polarizing names as “critical race theory” and “affirmative action”, there have been more dissidents to cultural pride - the men online who laugh at women of color and ask why everything has to be about race these days, the older white Americans who say that back in their day they didn’t see color, the teen girls who tell me that it’s cultural appreciation and they should be able to wear a qipao if they want. This, and the growing self-consciousness that is inevitable for most teenagers, forced me to confront a growing fear of mine: was I too Asian?

When I first listened to a K-pop song, I felt joyful, but ashamed. Perhaps it was too much to both be Asian and listen to Asian music. Was I becoming a caricature? By participating in so many aspects of my culture, was I to blame for how Asians are viewed in this country?

Almost as soon as these thoughts began to fester, we were plunged into the pandemic. I stayed inside and did my homework diligently, losing myself in YouTube videos from months past and hoping desperately that I would wake up and everything would be fine - the news reports on AAPI hate crimes would stop, the then-president wouldn’t call COVID the China virus, the world would exist outside my computer screen. But that didn’t happen for years.

All I remember thinking about during the first two years of the pandemic was my grandparents, and the homes I had on either coast. I read the news, checked Twitter, watched the TikToks my friends sent me, and woke up every day with the immense horror of how sickeningly possible it was for my grandparents to be killed that day for being Asian. I was haunted by the image of their heads smashed into the pavement in front of Dai Wong, the restaurant we bought roast pork and rice from. My mental health spiraled, even if I didn’t acknowledge it. I forgot about my internal struggle with my identity, focused instead on the survival of my loved ones.

When we came out of the pandemic and left survival mode, I once again faced the question of whether or not I was “too Asian”, but with a new perspective on the world. After years of fearing for my life and the lives of my loved ones, tired of questioning my place in Brookline and in America, I knew that to celebrate being Asian-American was an act of beautiful resistance. I refuse to deny myself the joy that is rooted in my heritage and in my memories, and I allow my pride to spread so wide as to reach the home that exists on either coast.

As the majority of this country begins to consider large concepts with such polarizing names as “critical race theory” and “affirmative action”, there have been more dissidents to cultural pride - the men online who laugh at women of color and ask why everything has to be about race these days, the older white Americans who say that back in their day they didn’t see color, the teen girls who tell me that it’s cultural appreciation and they should be able to wear a qipao if they want. This, and the growing self-consciousness that is inevitable for most teenagers, forced me to confront a growing fear of mine: was I too Asian?

When I first listened to a K-pop song, I felt joyful, but ashamed. Perhaps it was too much to both be Asian and listen to Asian music. Was I becoming a caricature? By participating in so many aspects of my culture, was I to blame for how Asians are viewed in this country?

Almost as soon as these thoughts began to fester, we were plunged into the pandemic. I stayed inside and did my homework diligently, losing myself in YouTube videos from months past and hoping desperately that I would wake up and everything would be fine - the news reports on AAPI hate crimes would stop, the then-president wouldn’t call COVID the China virus, the world would exist outside my computer screen. But that didn’t happen for years.

All I remember thinking about during the first two years of the pandemic was my grandparents, and the homes I had on either coast. I read the news, checked Twitter, watched the TikToks my friends sent me, and woke up every day with the immense horror of how sickeningly possible it was for my grandparents to be killed that day for being Asian. I was haunted by the image of their heads smashed into the pavement in front of Dai Wong, the restaurant we bought roast pork and rice from. My mental health spiraled, even if I didn’t acknowledge it. I forgot about my internal struggle with my identity, focused instead on the survival of my loved ones.

When we came out of the pandemic and left survival mode, I once again faced the question of whether or not I was “too Asian”, but with a new perspective on the world. After years of fearing for my life and the lives of my loved ones, tired of questioning my place in Brookline and in America, I knew that to celebrate being Asian-American was an act of beautiful resistance. I refuse to deny myself the joy that is rooted in my heritage and in my memories, and I allow my pride to spread so wide as to reach the home that exists on either coast.